This post is also published on the UW ICTD Blog here.

When it comes to frequency regulation, the FCC has to be strict — but its coarse-grained approach to licensing harms the small-scale hobbyist community. It could stand to learn a thing or two from the FAA on this issue.

Lately, I’ve been building a small-scale LTE network in our lab for testing. This network doesn’t use very much power, has a range smaller than my office, and is definitely stopped by any walls. This network is far too small, and too quiet, to bother any telecom operator — and yet, because LTE runs on a regulated frequency, it’s illegal for me to do this without an FCC license!

As we went through the licensing process, I started to notice a lot of interesting parallels between how the FCC regulates frequency and how the FAA regulates airspace: they’re both invisible (meaning you can commit a violation without realizing it), strictly regulated, and come with stiff penalties. Where they diverge, however, is the relationship with their DIY communities. The FAA heavily supports the general aviation community, and carves out airspace exemptions where possible to ensure that smaller airports and aircraft can continue to operate in an increasingly airline-dominated sky. Meanwhile, the FCC seems to have no such systems in place: frequencies are either completely licensed or unlicensed in an area, with no middle ground in between. Add this to expensive and complicated application forms, and it’s a perfect recipe for discouraging hobbyists and DIY experimentation.

How The FAA Handles Things:

A lot of people are familiar with the phrase “flying under the radar:” in common use, it means to do something discreetly, so as not to attract unwanted attention. What most people don’t know, however, is that the phrase also refers to a perfectly legal process designed for small aircraft and encouraged by the FAA itself.

When large airliners approach a major airport (like Sea-Tac, for example), the airspace they’re flying through is heavily controlled and monitored by Air Traffic Control (ATC). Starting about thirty miles away, the airliner must make radio contact and request permission to enter the airspace, at which point its movements are strictly dictated over the radio by Approach Control, who’re busy making sure that everything runs smoothly. While this high level of control is great for safety and helps keep planes on time, it also poses a serious challenge for smaller airports or airstrips that might be within that thirty mile radius. These small airstrips, which can be untowered or unpaved, are home to a wide range of small, local aircraft that have no interest in going anywhere near Sea-Tac. Meanwhile, the controllers at Sea-Tac already have their hands full with the airliners, and don’t want to talk to any airplanes they don’t have to.

The FAA’s solution to this problem involves a series of shelves. As airspace stretches farther away from the airport, the floor of the controlled airspace rises, leaving uncontrolled airspace below — literally “under the radar.” For an example, consider the University of Washington, roughly ten miles North of Sea-Tac. Over UW, Seattle Approach controls the airspace from ten thousand feet down to three thousand feet, but ignores anything below. This leaves plenty of room for small Cessnas to tour the city, fly from one airport to another, or just go out for flight lessons, without ever having to talk to Seattle Approach — and they’re perfectly legal, just as long as they stay under three thousand feet.

How The FCC Could Support Hobbyists:

The FCC application process isn’t the worst thing in the world, but it’s neither straightforward nor particularly easy to fill out. To be sure, they could probably make the process better, but there’s still a strong need for exemptions that would allow hobbyists, kids, and radio enthusiasts to play around without application forms or fear of breaking the law. Here’s a list of suggestions or ways that the FCC could better support the DIY community without disrupting bigger-scale ventures.

Idea #1: Waive regulation below certain signal strengths. Whether it’s AM/FM or cellular, a lot of hobbyists just want to make something work across the room, and then say “hey, we did it!” This kind of usage doesn’t interfere with anyone else, specifically because the signal’s at too low of a power to get very far. Granted, when transmitting something at such a low power, and over a relatively short distance, you’re not very likely to get caught — but it’s still explicitly illegal, and that’s a bit besides the point here.

Idea #2: Relax regulation on private property. The sum total signal strength of a radio signal degrades relatively quickly, at a rate of 1/r², with r being the distance to the antenna. If we also take walls and obstacles into account, this means that someone could broadcast a moderately strong radio signal inside their house without it bothering anyone outside. It’s easy to imagine an approach to frequency regulation that takes this into account, saying something like “you need to have a license to broadcast in public space, but anything you do in your own house is fine, just as long as you keep it below a certain signal-strength outside.”

Idea #3: Use a permissive, rather than restrictive, approach to licensing. Right now, we have an FCC experimental use application pending approval. The application is incredibly humble: we want to setup an LTE network inside a company’s headquarters, for a single day, on a single frequency band, to connect to a single cell phone, with a maximum radius of 15 feet.

Even though I know that this network isn’t going to bother anyone, we still had to apply, and are currently awaiting FCC approval. This process could be better served by a more permissive approach, wherein we could get immediate approval for our application, or a default answer of “yes unless we tell you no” as long as our application meets some certain criteria (e.g. kept indoors, or below a certain radius or signal strength). This way, the FCC is aware of the network, and still retains the option to say no, but operators can still move on with their lives in the meantime.

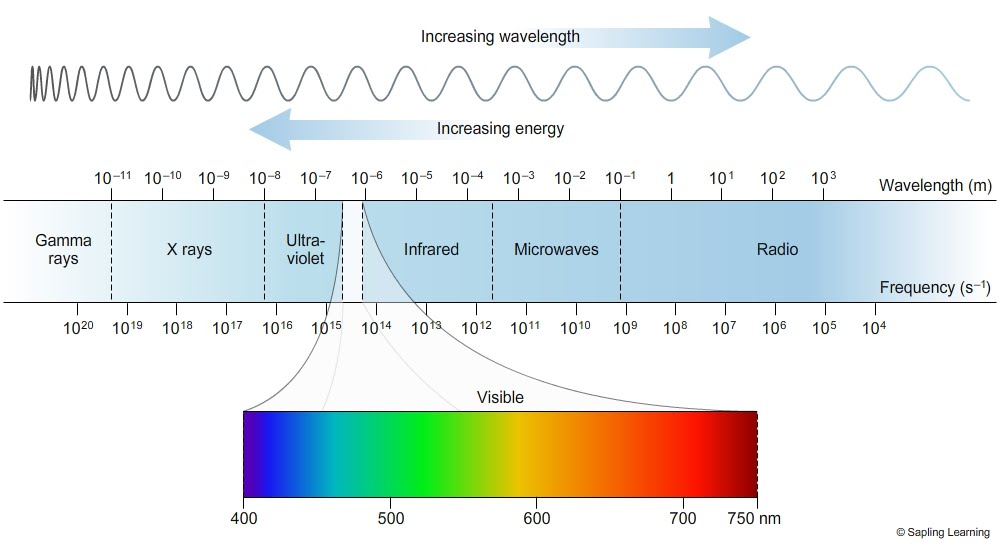

Idea #4: Create a basic, all-purpose “hobbyist” license. The suggestions above all stem from a core idea that if you’re careful, it’s not hard to stay safe and avoid disrupting other users. However, if the operator doesn’t know what they’re doing, it’s easy to screw up and broadcast on the wrong frequency, or at a much higher signal strength than desired. Even worse, since radio waves are invisible, there’s no clear or obvious indication that this is happening!

The FCC could reduce these risks by providing a basic operator or hobbyist licensing program. Rather than focusing on a specific type of radio protocol (e.g. AM/FM or LTE), the program could simply ensure that the operator understands basic radio principles, best operating practices, and how to stay in compliance. This idea could be paired up with the previous three, granting license-free permissions only to people who have demonstrated an understanding of and ability to comply with the restrictions placed on operation.

This system, if taken seriously and built out properly, could end up looking a lot like the FAA’s: pilots still need licenses to operate aircraft, but are allowed to go wherever they want as long as they know how to stay away from restricted areas. This approach to regulation has been vital to the general aviation community, which includes amateur pilots, flight instructors, students, and charter pilots. Similarly, I have no doubt that relaxing frequency regulations within a clear set of boundaries would be equally beneficial to the DIY radio community.